When love hurts

© Jessica Tutty for Auckland Therapy Blog, 1 May 2021

Anatomy of an Abusive Relationship

Anatomy of an Abusive Relationship

Domestic violence (including intimate partner abuse) is a serious problem in Aotearoa and is often referred to by the media as New Zealand’s “dirty little secret.” New Zealand Police receive a domestic violence call out, on average, every four minutes, totalling 328 call outs every single day. And that is just the tip of the iceberg. The vast majority of incidents are never reported.

When most people picture an abusive relationship, they think of the atrocities committed by Jake Heke in Once Were Warriors; how he would lose his temper and push, shove, punch and strangle his wife, Beth. Many of us believe that, for a relationship to be considered ‘abusive,’ it must include this type of serious physical abuse. This is a myth. Intimate partner abuse can take many different forms.

When is a relationship considered abusive?

It has been found that partner abuse almost never consists of a single, isolated incident and instead involves a pattern of coercive control. Instances of violence are just one element of a complex web of tactics used by an abusive person to subjugate their partner and maintain the ‘upper hand’ in the relationship.

Coercive control refers to a pattern of controlling behaviours which create an unequal power dynamic in the relationship, giving one partner power over the other and making it difficult for them to leave. Being fearful of what your partner might say or do is linked to coercive control.

The presence of fear in a relationship is the most reliable indicator that the relationship is abusive.

Evan Stark, who first coined the term “coercive control,” asserted that the level of coercive control in an abusive relationship offers a more accurate predictor of future sexual assaults and severe/fatal physical violence, than the presence of prior assaults.

Whilst anyone can experience coercive control (and intimate partner abuse), it is far more common for males to exhibit this behaviour against female partners. This is because coercive control is most often grounded in gender-based privilege whereby men feel entitled to a sense of power and control over women. NZ Police figures state that males account for 85% of those arrested for family violence offences and 98% of those arrested for sexual violence offences.

It is also important to not forget the LGBTQI community, as recent studies have found that gay, lesbian or bisexual people are more than twice as likely as heterosexual people to suffer from sexual violence or family harm. Being part of a minority creates additional stress from both external and internal pressures, such as invisibility, isolation and discrimination, resulting in negative self-beliefs, damaged self-esteem and increased relationship conflict.

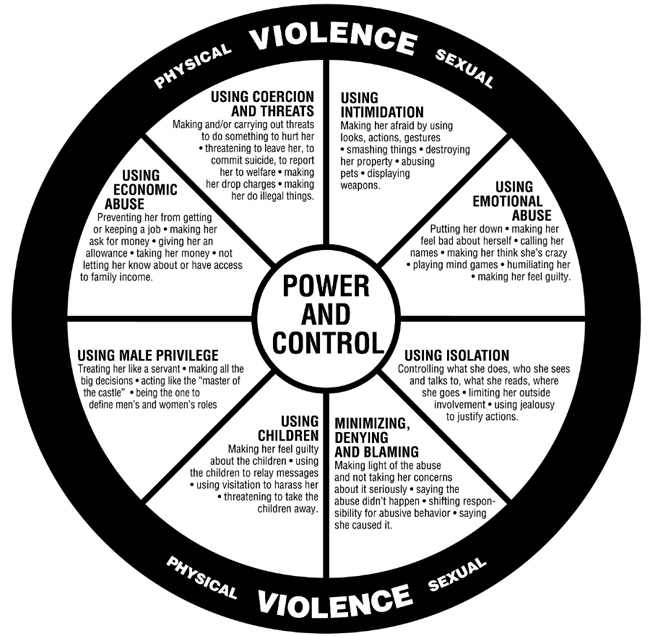

The Power and Control Wheel

The Power and Control Wheel (see below) was developed in the early 1980s by Ellen Pence, Michael Paymar and Coral McDonald in Duluth, Minnesota as a part of their Domestic Abuse Intervention Project. Pence, Paymar and McDonald spoke extensively with groups of women who had experienced domestic violence in intimate partner relationships and used these women’s input as the sole basis for the development of the model.

The Power and Control Wheel outlines the more constant, insidious, everyday abusive behaviours (or tactics) used to gain and maintain coercive control in abusive relationships (in the inner circle), along with the more readily apparent instances of physical and sexual violence (in the outer circle). These abusive behaviours/tactics do not occur in isolation from each other, but rather occur simultaneously. They include:

- Using coercion and threats: Controlling through making and/or carrying out threats to do something which would harm your partner in some way (i.e.: threatening to leave the relationship, commit suicide or report them to the authorities if they do not comply with your wishes).

- Using intimidation: Acting in certain ways in order to elicit fear in your partner (i.e.: punching walls, destroying their belongings, communicating in an aggressive manner).

- Using emotional abuse: Engaging in behaviours designed to make your partner feel bad about themself (i.e.: putting them down, name-calling, denying their reality, guilt-tripping and humiliating them).

- Using isolation: Controlling and limiting what your partner does and their involvement with people other than you (i.e.: policing who they see and talk to, what they read and where they go, using jealousy to justify your actions).

- Minimising, denying and blaming: Downplaying the abuse, not taking your partner’s concerns about your behaviour seriously and blaming them for your actions (i.e.: saying the abuse didn’t happen, they are overreacting or that they caused it).

- Using children: Controlling your partner through the children (i.e.: threatening to take the children away or making them feel guilty for upsetting the children by questioning the abuse/leaving the relationship).

- Using male privilege: Using your gender to justify your right to control your partner (i.e.: telling them what to do, being the one to define men’s and women’s roles, making all of the important decisions by yourself).

- Using economic abuse: Limiting your partner’s independence through limiting their access to money (i.e.: preventing them from getting or keeping a job, not letting them know or have access to family income, giving them an allowance or making them ask you for money).

It is important to note that, whilst there can be variations in the severity of these behaviours/tactics, generally if one or more of these are present in a relationship, there is a significant risk of the partner who is being controlled becoming traumatised.

Physical or sexual abuse is not necessary for traumatisation to occur. The coercive control behaviours/tactics (listed above) are inherently traumatic in and of themselves.

The Cycle of Abuse

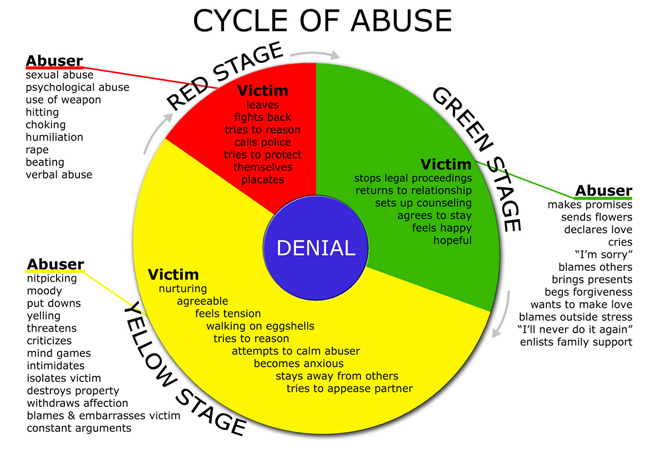

People are often unsure if their relationship is abusive because their partner only displays abusive behaviours or assaults them sometimes, while the rest of the time the relationship can feel relatively normal (or, at times, even happy). This is because almost no partner is abusive all the time, abuse usually happens in a cycle. For the sake of simplicity I will explain this cycle in terms of the colours of a traffic light.

The RED Stage / “The Explosion”: This is where a significant abusive event (or events) occurs, whether it be verbal, physical, sexual or psychological. Here the victim will typically either fight back, leave, try to reason with or placate their partner, try to protect themselves and their children, pets (or other vulnerable parties) and possibly call for help (from Police, neighbours, friends or other family members).

The GREEN Stage / “The Honeymoon”: This is where the abusive person makes attempts to repair the damage caused to the relationship by “The Explosion.” This could include begging for forgiveness, promising that it will never happen again, blaming others/stress, making a big romantic gesture and enlisting (or promising to enlist) external support. More often than not, the declarations of love and the promise of changed behaviour means the victim feels happier and more hopeful and decides to stay in the relationship, putting a halt to all legal proceedings (if charges have been pressed).

The YELLOW STAGE / “Tension Building”: This occurs when “The Honeymoon” wears off and the abusive person begins to engage in coercive control behaviours. This could include making threats, using isolation, intimidation, minimising, denying and blaming, emotional abuse etc (see the Power and Control Wheel). This phase is generally turbulent and characterised by frequent arguments and constant tension. The victim’s anxiety levels rise and they “walk on eggshells” in an attempt to avoid an inevitable abusive event occurring.

Of course, when the tension reaches boiling point, another significant abusive event (or (“Explosion”) occurs and the cycle repeats itself and keeps repeating until the victim is able to break out of the cycle and leave their abusive partner. Whilst the victim’s denial of the abusive nature of their partner contributes to keeping the cycle repeating, unfortunately, leaving the relationship is often difficult and dangerous and there are many understandable reasons why victims don’t leave. It has been found that women are most likely to be murdered by their abusive partner right after they leave the relationship, rather than while they remain in it.

Whilst it is not unheard of for people with entrenched abusive behaviours to successfully change their ways and cease their abusive behaviours, it is the exception rather than the rule. This requires a great deal of work and commitment from both parties in the relationship, extensive professional assistance and an undetermined, lengthy period of time. Indeed from an early age, many boys are taught to deny their feelings and value competitiveness, toughness and independence. This means men are less likely to acknowledge any vulnerability or to ask for help and can react quite differently to women when they are struggling. Consequently meaningful growth and change can be a long road. See our Men's counselling page.

I am in an abusive relationship – now what?

Whilst this can be a daunting and devastating realisation to come to, please know that you are not alone and that help is available. Making the decision to challenge the status quo and address what is happening can often be the most difficult, but significant part of the process. If you have gotten this far, you are already well on your way to a new, safer, more peaceful way of living. It is now vitally important to surround yourself with a strong, reliable support system to help you through this transition period. You may want to consider the suggestions below:

- Let someone you trust know what’s going on: This should be somebody who you trust to listen to you (rather than judging or telling you what to do), as well as someone who is able to be there for you when you need their help and/or support. This could be a friend, family member or work colleague.

- Make a safety plan: Ensure you have a plan (preferably written down) for what you will do the next time abuse occurs and you find yourself in the RED Stage of the cycle. This should be kept in an easily accessible (but private) place and include phone numbers of who you can contact (your support people, emergency services and specialist family violence services) and where you can go if you are feeling unsafe and scared. It can help to get familiar with your next-door neighbours as they are close by, so will be well-suited to assist if needed.

- Get familiar with the specialist support services near you: There are some great domestic violence support services available in New Zealand, including Shine who provide a free national domestic violence hotline service (0508 744 633 from 9am-11pm, 7 days a week), as well as support and advocacy and access to women’s refuges. For more information visit 2shine.org.nz. The full list of services available in your region can be searched via family.services.govt.nz.

- Seek professional help: Working with a therapist can also be very beneficial as it provides a professional third party’s assistance in keeping you as physically and emotionally safe as possible. Therapy also provides a safe, confidential and regular space to work through your feelings about your relationship and your past and present trauma.